Pinpointing Policy: Reference Prices Will be Increasing, But is it Enough?

Published

10/9/2023

A farm bill issue often discussed over the last year or so are reference prices. Essentially, we want them increased. American Farm Bureau Federation (AFBF) policy 239 /National Farm Policy, Farm Bill Principles under we support, states, “8.2.1.1.4. A reference price increase for all Title I commodities.” This position is universally held, not just by Farm Bureau, but several commodity organizations are also calling on Congress to increase reference prices. But getting them increased in the current political and budgetary environment will likely be a heavy lift for ag lobbyists and farm-state congressmen.

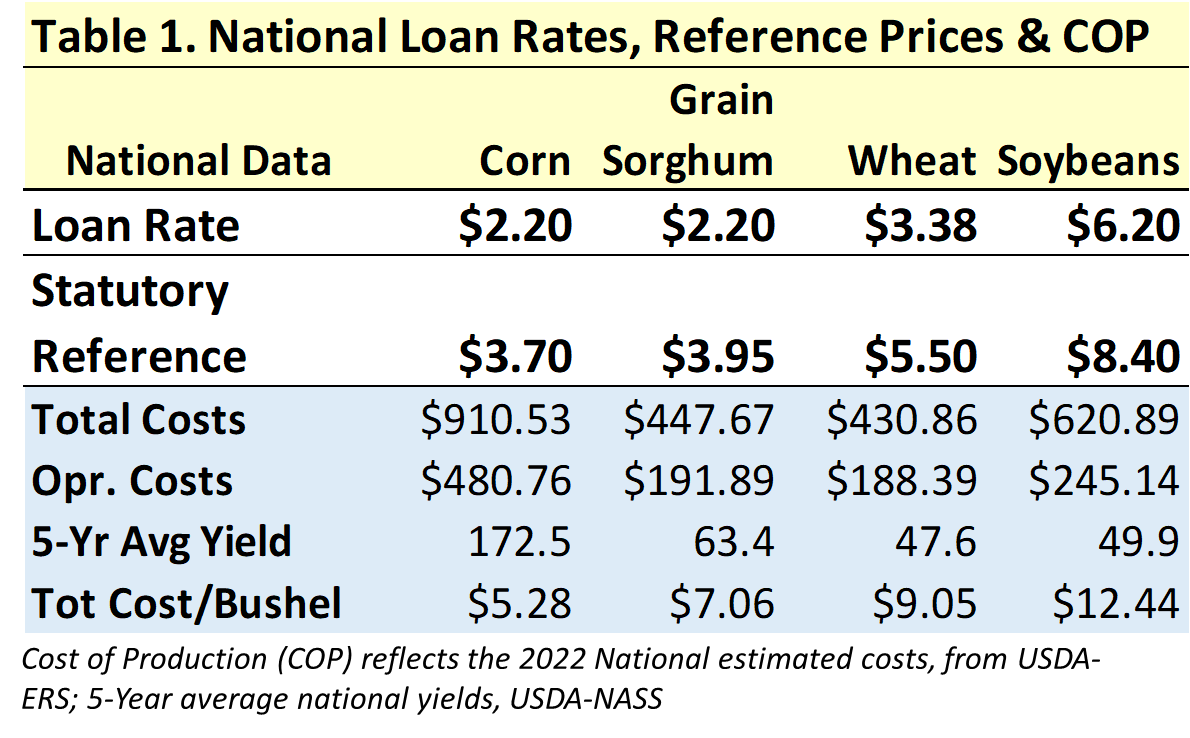

Currently, there are 19 Title I commodities, but for the purposes of this article, we’ll focus on the four that garner the most acres in Kansas: wheat, corn, grain sorghum and soybeans. As Kansas farmers are well aware, production costs have risen substantially over the past several years, which is why we’re asking for increases in farm safety net triggers. Table 1 reflects national farm program data, along with estimates of enterprise costs of production, showing that 2014 statutory reference prices are arguably not keeping up with today’s costs of production.

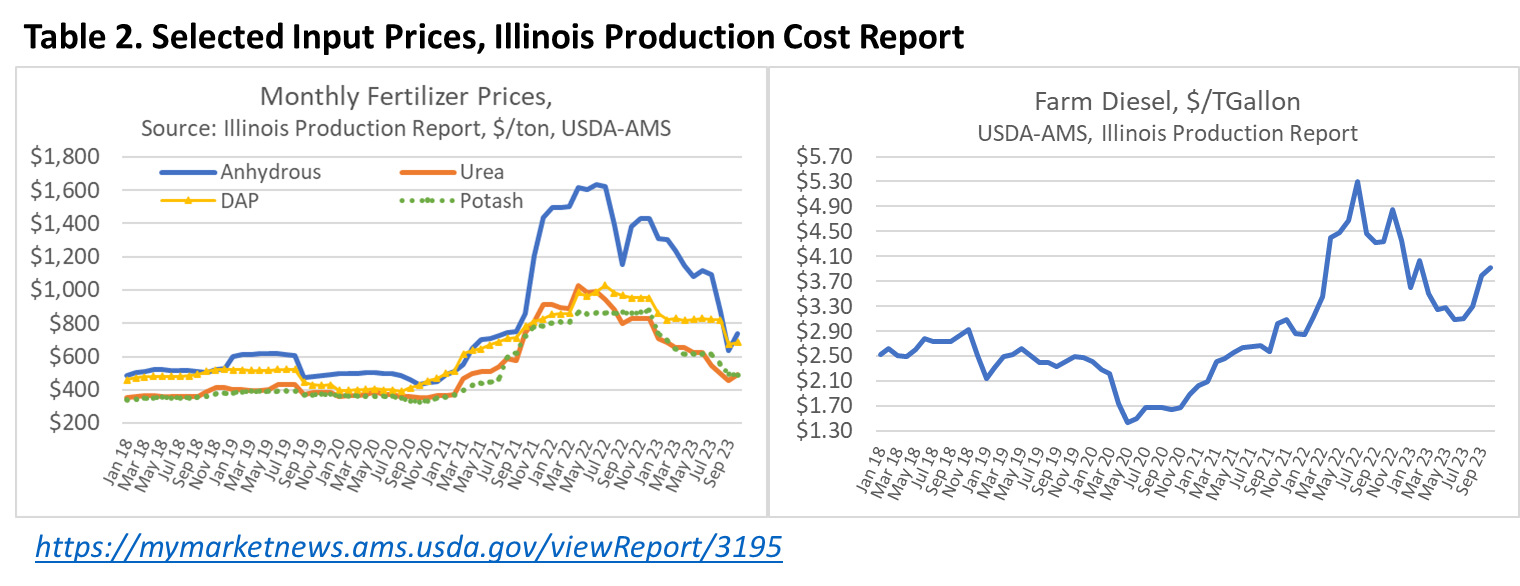

And inflation is sticky. While some input prices have decreased relative to 2022, both fertilzer and diesel prices remain above 2018-2019 levels and diesel has increased $0.80/gallon since July of this year.

As we stated in the title, reference prices will be increasing, but is it enough? By definition, reference prices are the prices for covered commodities set in Title I of the 2014 farm bill, rolled forward into the 2018 farm bill and used in the Price Loss Coverage (PLC) and Agriculture Risk (ARC) programs, as part of the triggering mechanisms signaling when safety net payments will be available.

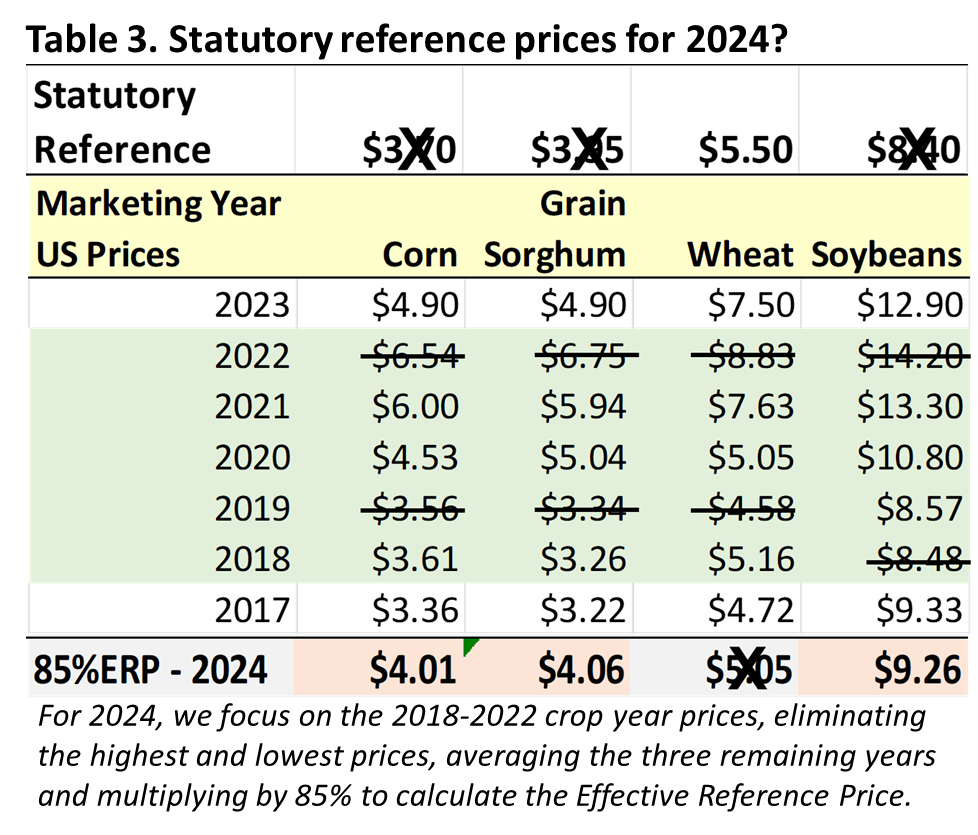

In the 2018 farm bill, Congress added an effective reference price (ERP) calculation to the PLC program (P.L. 115-334). The ERP provides a mechanism to temporarily increase the price trigger in the program provided by the statutory reference price (SRP) when marketing year average (MYA) prices are high enough for multiple years. Specifically, the ERP calculation is the larger of the SRP or 85 percent of the five-year Olympic moving average of MYA prices (but not to exceed 115 percent of the SRP). More on this has been written about by our friends at farmdocdaily.1 Table three provides estimates and a depiction of this calculation for 2024. Substituting the greater prices observed in 2022 for the lower prices of 2017, suggest greater effective reference prices versus statutory levels in corn ($4.01), grain sorghum ($4.06) and soybeans ($9.26) for 2024. For wheat, 85 percent of the Olympic average of prices only results in a price of $5.05, much less than the statutory price of $5.50. Note: all of these suggested 2024 reference prices (corn, grain sorghum and soybeans) are less than their 115 percent caps: corn ($4.26), grain sorghum ($4.54), soybeans ($9.66) and wheat ($6.33).

Policy Questions to Ponder

- Should farmers and ranchers pursue policy that would seek adjustments in how ERPs are calculated? For example, reccommending 90 percent be used instead of 85 percent would result in 2024 calculated prices of: corn ($4.24), grain sorghum ($4.30), soybeans ($9.77) and wheat ($5.35). Note that soybeans would exceed the 115 percent cap, resulting in a $9.66 reference price, and wheat, unfortunately, would still result in the statutory level of $5.50 for a reference price;

- Should farmers and ranchers pursue policy that would seek an increase in the 115 percent cap? Looking forward to the effective reference price calculations for 2025, 2023 crop year prices, will be added, and are currently estimated at levels greater than those in 2018 (which will be removed from the calculations). If WASDE estimates hold for 2023, then very tentative calculations of, “85 percent of the Olympic average,” result in corn ($4.37), grain sorghum ($4.50), soybeans ($10.48) and wheat ($5.72); with both corn and soybeans exceeding the 115 percent cap, meaning their reference prices would instead be $4.26 and $9.66 respectively, wheat though, would finally see an increase; or

- Should farmers and ranchers simply continue to pursue policy that would seek increases in statutory reference prices?

The current self-adjusting, effective reference price calculation is reflective of market forces. As prices increase, our safety net adjusts upward, and yes, as market prices decrease, the safety net will also adjust downward. The benefit of this is it allows farmers to adjust and plant to the market, as opposed to statutory prices that may or may not accurately reflect current market fundamentals. AFBF policy 239 / National Farm Policy, 2, states, “We support a consistent, long-term, market-oriented farm policy that will:

2.1. Rely less on government and increasingly more on the market as well as providing more options for insurance and revenue assurance products that are more equitable for all commodities in all production regions of the country against adverse market fluctuations and weather-related hazards;

2.2. Support farmers during times of market disruption based on gross revenue and cost of production;

2.3. Allow farmers to take maximum advantage of market opportunities at home and abroad without government interference;

2.4. Encourage production decisions based on market demand;

2.5. Develop risk management tools to deal with the inherent fluctuations in revenue and income associated with farming;

2.6. Provide strong and effective safety net/risk management programs that do not guarantee a profit, but instead protects producers from catastrophic occurrences while minimizing the potential for farm programs affecting production decisions;

2.7. Comply with World Trade Organization (WTO) agreements;

Making changes to statutory reference prices may not be as easy as it appears. First, it could be very expensive and difficult for farm-state legislators to push through, and if set too high, it could provide planting incentives out of sync with market forces.