Pinpointing Policy: The Impacts of Tariffs

Author

Published

10/3/2024

Tariffs have been a significant topic during the 2024 presidential campaign. Is it an all-purpose fix to what ails America or a sales tax on the American people? Let’s take a closer at tariffs and examine the potential impacts they might have on agriculture.

By definition, a tariff is a duty or tax imposed on imported goods by a government, either a set amount or more often, a percentage of value. Current campaign rhetoric is focused on the U.S. imposing tariffs on goods brought in from other countries.

Let’s outline a simple tariff example. Walmart may find the least costly sweatpants in the world are manufactured in Thailand, and as a result, negotiates to purchase sweatpants from a factory in Thailand. To protect American manufacturers, the U.S. imposes a tariff. When the product arrives, the manufacturer/seller would pay a “tariff,” to the U.S. government, as they bring it through U.S. customs. This increases the cost to get it into the U.S., it is not a tax on Thailand.

From an economic standpoint, tariffs are designed to support domestic prices and by extension, domestic producers. For example, this imaginary tariff effectively raised the price of imported sweatpants, and now Walmart may find that U.S. made sweatpants can be obtained at an equal or lesser price to imported sweatpants. Walmart would likely begin sourcing them domestically, which would clearly help U.S. manufacturers, but at the end of the day, your Walmart sweatpants will now cost you more than they did prior to the tariff. The Peterson Institute for International Economics estimates increased tariffs of 10 to 20 percent on most U.S. imports and 60 percent on imports from China will cost American households between $1,700 to $2,600 per year.

Historically, U.S. agriculture and Farm Bureau, have viewed tariffs as a protectionist measure, and our negotiating goal has been to reduce and ultimately eliminate tariffs on U.S. exports.

AFBF Policy #252 / International Trade1, line number 1., states, “We are strong advocates of fair and open world trade,” and under section 4., Agricultural exports will be increased by, [line 4.9] “Lowering overburdensome/unreasonable tariffs on agricultural products, especially those products other countries are not producing,” and 8.5 states, “We support limiting trade disruptions and resolving trade disputes through negotiations, not tariffs or withdrawals from other trade agreement discussions.”

But trade is a complicated endeavor and Farm Bureau policy #252 / International Trade, line 9.12. says, “We oppose tariff reductions if it results in creating an oligopoly.” Or, a market with a small number of producers or sellers, and thus little competition.

Do tariffs harm exporting counties? Potentially but indirectly. For example, if the hypothetical sweatpant factory can’t replace the sales to the U.S. lost due to tariffs, they may have to lay off workers or even close down. This would most definitely impact the government of Thailand, as tax income would fall and unemployment would increase.

Can tariffs be used to promote U.S. production? Potentially and slightly, but at what cost? In the above example, the shortrun cost of sweatpants to U.S. consumers went up. With the added Walmart business, would U.S. sweatpant makers expand production? Likely. Would that create a surplus, and thus drive down prices? Maybe, but do we really believe that?

In 2018, the United States imposed Section 232 tariffs on steel and aluminum imports from major trading partners. Domestic U.S. steel production increased into 2019 and while those tariffs largely remain, steel production has since drifted lower, back to pretariff levels. In fact, one company, United States Steel, still remains unprofitable and is choosing to merge with Nippon Steel of Japan.

Coming back to today’s super-charged campaign rhetoric, Farm Bureau’s message on tariffs is we are very concerned about imposing them. In fact, Farm Bureau is currently opposing Commerce Department efforts to impose countervailing duties (i.e., a tariff to counteract the effects of foreign subsidies) on imports of 2,4-D from China and India. U.S. demand exceeds domestic production, imports fill the gap in supply and keep the price of this important tool in the farmers weed management toolbox more affordable.

A bigger concern with imposing widespread tariffs, particularly on China, is they may well result in retaliatory tariffs that would likely decrease our agricultural exports. For example, remember those 20182 Section 232 tariffs on steel and aluminum imports? At the same time, the U.S. imposed Section 301 tariffs on a broad range of imports from China. In response, Canada, China, the European Union, India, Mexico and Turkey imposed retaliatory tariffs on many U.S. exports, including a wide range of agricultural and food products, ranging from 2 to 140 percent.

- The retaliatory tariffs increased the price of U.S. agricultural exports in these markets relative to our competitors.

- U.S. agricultural exports significantly declined, leading to increased domestic supplies and sharply lower prices paid to farmers.

- The administration worked to assist farmers hurt by the retaliatory tariffs by creating the Market Facilitation Program, which provided $23 billion to farmers over 2018 and 2019, according to the Government Accountability Office (GAO). Farm Bureau lobbied for this assistance behind AFBF Policy #252 / International Trade, line 3., that says, “We support federal assistance for producers who have been impacted by retaliatory tariffs. Furthermore, to the greatest extent possible, such assistance should be distributed proportionally to all impacted producers. U.S. officials should ensure such assistance is distributed equitably based on commodity and payment calculations that are determined by production history and not a total of agricultural production in the county.”

- On Jan. 15, 2020, President Donald Trump and China’s Vice Premier Liu He signed a “Phase One” trade agreement to end the tariff war, with China agreeing to purchase $80 billion in agricultural products over 2020 and 2021. Ultimately, China bought $62 billion, and U.S. market share has yet to fully recover to pre-retaliatory levels.

Going further back, in 1930, the U.S. passed the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act, which set U.S. tariffs at some of their highest levels ever. Other countries retaliated; world trade plummeted by two-thirds from 1929-1934; and in part was responsible for deepening and lengthening the Great Depression.

Maybe the bigger question is, why do we trade?

In 1776, Adam Smith, a Scottish economist, philosopher and author wrote, “It is a maxim for every prudent master of a family, never to attempt to make at home, what it will cost them more to make, than to buy. The tailor does not attempt to make their own shoes, but buys them of the shoemaker3.”

David Ricardo, another classical economist, built on Smith’s work, and his “Law of Comparative Advantage” suggests countries can benefit from trade by specializing in producing goods where they have a relative advantage, even if another country is better at producing everything overall. Making the case that the efficient use of resources, plus trade, results in greater prosperity, raising incomes and lowering costs to all.

We in agriculture support agricultural trade and the concepts of free and open markets because American farmers have a comparative advantage. The U.S has roughly 10 percent of the world’s arable land and slightly more than 4 percent of its population. Kansas, with roughly 21-million acres of harvested cropland and another 15-million acres of range and pasture, has WAY more agriculture capacity than our 2.9 million citizens can consume. And between you and me, American farmers are the best you’ll find anywhere in the world. U.S agriculture clearly has a comparative advantage, and the world benefits when the U.S. produces and when we trade. That’s why AFBF Policy #252 / International Trade, line 2., states, “Aggressive efforts must be made at all levels to open new markets and expand existing markets for U.S. agricultural products.”

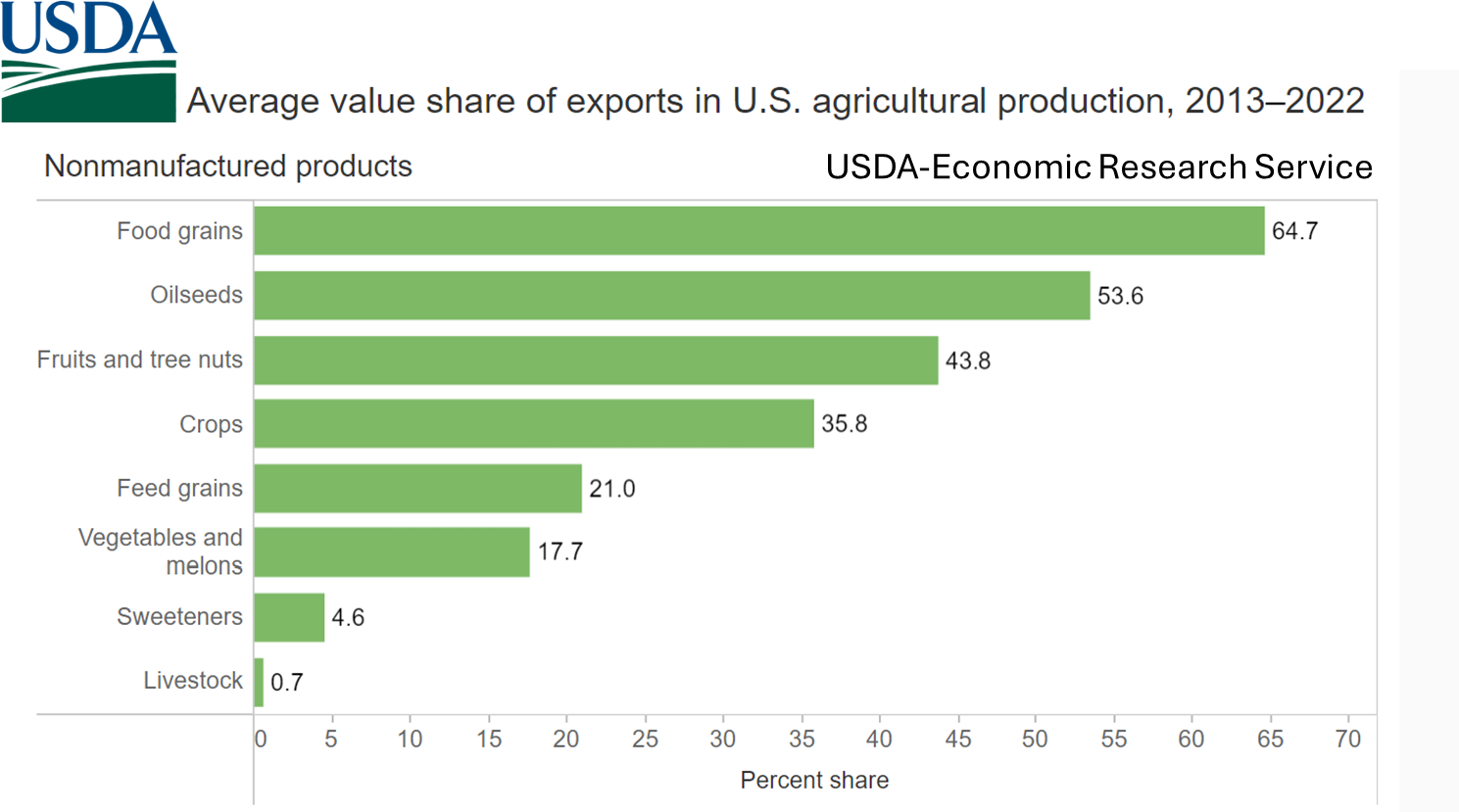

American Agriculture depends on trade.

Source: U.S. Agricultural Trade at a Glance

The Office of the United States Trade Representatives, Glossary of Trade Terms.